Story

Sept. 2013. Two and a half years since the Great East Japan Earthquake, monitoring posts installed in many corners of Iwaki indicate the level of radiation. The local radio announces the amount of radiation at a fixed hour every day.

In the city, the dialog meeting, “Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) in Iwaki”, is being held. There are about 60 participants from many different age groups. The theme today is “What I think and feel two and a half years after the earthquake disaster”. Groups of about 3 or 4 sit at a table and start the dialog by recounting their memories of the earthquake.

“I couldn’t stay standing.” “I was concerned about food.” “The house did not collapse, but I fled from Iwaki because I was afraid of the nuclear power station.”

“My memory of the order of events for the 6 months after the catastrophic earthquake is vague.” Shinko Shimomura, a father of 3 children and the Deputy Priest at Bodai-in Temple, says.

“There is no escape from the radiation contamination problem. If that is the case, I want to do the best I can for the future of our children.”

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), each person talks about one’s experience as if he/she were giving a self-introduction.

“At college, when I’m asked where I’m from and I tell them I’m from Fukushima, the most common response is “Are you OK?” It makes me feel a little uncomfortable.”

“The area I live in, the radiation level is low and so I don’t really consider myself a victim.” “I’d like to keep my mind neutral by listening to other people’s opinions, so that I won’t be biased.”

Together with her schoolmates, Aoi Seto, who goes to a high school in the city, is creating a CM to attract tourists to Iwaki. It is a project in collaboration with a travel agency.

“The realization that I am on the side that is telling people about the catastrophic earthquake led me to act.”

At one of the tables, the discussion is “How should we take in the current situation?”

“Perhaps we’ve come to a point where we should stop saying ‘Oh, no, no, no!’ and start voicing some positive attitudes.” “I believe that now is the turning point when the world is changing. The truth is that there are people smiling behind the people who are wailing that things are terrible.” “It just depends on how one can actually turn a bad situation into a good one.”

“I think we’ve all prepared ourselves for the worst and having done so, we are trying to think of ways to move on with our lives.” Yuichiro Kobayashi, the owner of a surf shop, has been clearing the Tsunami debris moments after the earthquake and has watched over the sea ever since. He conducts water quality inspections himself, but is concerned about the contaminated water draining into the sea from the nuclear power station.

“ Whether it’s local or out of the prefecture, people who have a passion for surfing will go out to surf if there’s a sea with waves.”

Seiji Nakamura, a fellow-surfer, is a photojournalist. At the beach, he showed us photos of scenes right after the earthquake hit.

“The town by the beach was burning as if it had been air-bombed. It was really terrifying.”

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), people change seats and continue their dialog. The participants say that by telling the people at another table about what they had talked about with the previous group, the dialog becomes deeper and is shared at the same time.

“Compared to before the earthquake, the big difference is that I am able to say what I really feel.” “Since the earthquake, the true nature of relationships with other people has been revealed.” “After the earthquake, we were blessed in many ways. Although I still have anxieties, I feel quite happy.”

“I’d like to find something that has come to being because of the earthquake.” Takeshi Matsumoto says. He is the one that started the Yoake-Ichiba, a restaurant district where shops full of energy and determination to boost and liven up Iwaki stand side by side.

“I’ve come to believe that if there is something I want to do, I should do it when I can. I intend to live my life to the fullest.”

At the stand-up bar Momo in the Yoake-Ichiba, Momoko Aikawa stands behind the counter, even though she is over 80 years old. She says that many of her regulars died in the earthquake.

“I am finally able to slowly talk about the earthquake. We’re all still trying so hard. It was only 2 years ago.”

The liveliness of the city of Iwaki in the past is a popular topic at the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting). The production of coal used to be the city’s key industry. “There used to be 3 department stores in the city. The coal mining and fishing industries were really big.”

“When I joined the company, it was right in the midst of changing its trade.” In 1966, when Kazuo Nogi joined Joban Coal Mine, a resort facility was opened. The company decided to shift its trade from coal mining to tourism.

“Since the olden days, the Joban region has been the supply depot for the Metropolitan area. Coal in the past, now nuclear energy.”

“There used to be huge crowds everyday.” Even to this day, the Hula Dance Show continues to be the star attraction. Remembered are the opening days, which became a movie featuring the first generation hula girls.

“It was the policy of the then president to hire the ladies of the miners. The closing of the coal mine was definite, and so the band musicians were also people from the mines. It was, in effect, an employment strategy as well.”

At “The Hula Girls Koshien Championship”, which started the year of the earthquake, high school hula girls across the country come to Iwaki to compete.

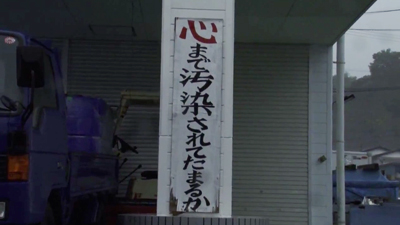

This is a signboard with a slogan saying to stand up against the nuclear power station accident. A rally to protest against the nuclear energy policy was being held in the station square.

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), there are many different attitudes toward the issues concerning the nuclear power station accident.

“I am so scared that there might be another accident at the nuclear power station.” “Why are they re-starting under these circumstances?” “The problem has not been solved yet.” “In my everyday life, I pretty much don’t look at the surveying instrument.” “As far as the radiation issue is concerned, there is no way to obtain a definite answer.” “I even have some regrets about the fact that I had not given it any thought until the accident happened.”

“If the radiation levels of the harvested agricultural products are below the accepted standard, some farmers ship the products to the market, but won’t eat them themselves.“ Says Yutaka Maruyama, who is a farmer that grows fruits in the city.

“When there is a shipment restriction, the one conveying the message speaks out loud and clear, while the receiver also listens intently. But the fact that a restriction has been lifted is made known to far fewer people than one might expect.”

“Whenever there was news of a shipment ban, however hard we tried to appeal that it wasn’t about us, many orders were cancelled.”

The nameko mushrooms that Naomasa Kamo grows are praised by dealers for its high quality, but he is still unable to break away from the effects of the accident. “The market price is still half or less than half of what it used to be before the earthquake.”

Fishery is also another one of Iwaki’s main industries. Ever since the nuclear power station accident, fishery remains shut down. At Kunohama port, fishermen work on the maintenance of their boats waiting for the trial fishing to begin. “In the bid for the Tokyo Olympics, they claimed that Tokyo is 200km away from Fukushima. That only means that they are going to abandon Fukushima.”

“I wonder if people would eat the fish we catch…” Then, he asked the students who were doing the interview, “How about it? Would you people eat them?”

There is not a soul at the fresh fishmonger. “I don’t sell fish from Fukushima at all and I carefully handpick my products. But still, no customers.”

“It’s not that I want somebody to do something about it. I just do what I do, one day at a time, thinking of how to go about this.”

In many parts of the city, election campaigns for the city mayor to be voted in a few days were going on.

Children can also be seen taking part in the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting).

“Which are you more afraid of, the earthquake or radiation?” “Well, the tsunami!” “I’m not that scared of radiation. There isn’t much of it now, right?”

Next to them, at the adults’ table, the topic is about the difficulties of raising children in Iwaki.

“My child said to me, ‘Why did you have a baby at a time like this?’” “Some parents want to let their kids play outside even if there are some risks, but some are absolutely against it.” “There are over 450 parks in the city, but only 11 have been decontaminated.”

“I came back from the place of refuge thinking that if we were careful, things should be alright.” Yoshida, who has a grade school daughter, tries to stay positive, but through the dialogs, she realized that she, too, is harboring anxieties.

“At home, she’s climbing trees that haven’t been decontaminated. But I think physical exercise and being stress-free are good things.”

“We don’t know if it’s from the radiation or not, but cysts have been detected in both my child’s and my thyroid glands.” Suganami is a lawyer and a mother of 5 children. She would like to avoid radiation as much as possible, but there is something on her mind that she keeps bothering her.

“Some people go about concerned about the radiation. But then, there are some that look away from the issue, or don’t even want to talk about radiation. They both have the right to freedom.”

Masako Ono, the director of a day-care center for children, says that she did everything she could, such as renewing the garden soil after the nuclear power station accident, to minimize the effects of radiation on the children.

“The reason why I decided to open the center 2 weeks after the accident was because there were people who could not move out of Iwaki. We have to accept that reality.”

The facilitator in charge of leading the meeting asks the participants.

“Many topics are being talked about. Having talked about them, what sort of a future do you have in mind?”

“It is definitely important to provide care for the children, but we must think of the grown-ups as well.” Kakuhisa Ono was working at a Junior High School near the shore when the earthquake struck. From a hilltop where he evacuated with the students, he witnessed the tsunami hit the villages.

“The children seem to be more emotionally hurt by the agonizing situation that their parents are in than about themselves.”

“In case of an earthquake, I had it ingrained in me that my job was to first and foremost convey the information to everyone.”

Michiko Sakamoto, who announced the occurrence of the earthquake on FM Iwaki, provided a lot of information through the radio right after the quake. “As time went by, there were unidentified dead bodies which had been severely disfigured, and I struggled to find appropriate words to convey these in the context of a regular program.”

“We are going to do something about what happened in our time. I’m glad it didn’t happen in our children’s era.” Hirokazu Ishii, who runs a fishing boat business, lost his father and beloved daughter in the tsunami.

“I was able to save my boat, but somewhere in me, I feel that because of that I lost my family. That’s why I am searching for the meaning of why I saved this boat.”

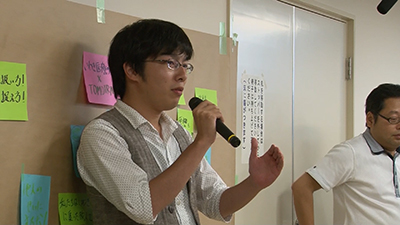

After the talking is over at the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), it is time for the results. Words by each participant are written on notepapers of different colors and posted on the wall.

“How to deal with and how to perceive the wall” was written by a college student who took part. Having said that there are many walls in Iwaki, he pointed out that the biggest one is the wall that stands between the people who have fled to Iwaki from other towns and the original citizens of Iwaki.

In the Izumi district of the city, there is an emergency temporary housing of 200 units in which evacuees from Tomioka-cho live.

“I love to cook”, says Shizue Sato, who lives alone in the temporary housing. She cannot help feeling homesick about the town where she used to live with her late husband.

“Of course I think about the house we worked so hard for. I want to go back and die in my own house. But I’m too old and I don’t know how much longer I can live.”

Mr. & Mrs. Nishihara play a leadership role among the resident volunteers. The husband, Kiyoshi, worked for a company affiliated with the nuclear power station. The wife, Chikako, thinks, though it was a dreadful accident, that they should not blame it all on Tokyo Electric, since they had, in some aspects, accepted its presence, too.

“I think it’s about time we stopped being sorry about what we’ve lost. If we count the things that we are left with and what we’ve gained since, they will lead us into the future.” After she said so, she sang us a Tomioka-cho folk song.

“It’d be nice if each person’s experience is passed on to future generations as individual stories.” Hikari Fujishiro, one of the promoters of the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), continues to work on compiling the earthquake disaster experiences he has collected through interviews. About a month after the earthquake, he was inspired and has since been working on the project with his supporters.

“Being aware of the changing generations, I’d like to continue the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) and the interviews for about 30 years.”

January, 2014. People clad in warm winter clothes are gathering at Bodai-in Temple. The Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) 2014 has started.

Among the familiar faces, there are some new faces, too. The next dialog for the future has begun in Iwaki.

Sept. 2013. Two and a half years since the Great East Japan Earthquake, monitoring posts installed in many corners of Iwaki indicate the level of radiation. The local radio announces the amount of radiation at a fixed hour every day.

In the city, the dialog meeting, “Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) in Iwaki”, is being held. There are about 60 participants from many different age groups. The theme today is “What I think and feel two and a half years after the earthquake disaster”. Groups of about 3 or 4 sit at a table and start the dialog by recounting their memories of the earthquake.

“I couldn’t stay standing.” “I was concerned about food.” “The house did not collapse, but I fled from Iwaki because I was afraid of the nuclear power station.”

“My memory of the order of events for the 6 months after the catastrophic earthquake is vague.” Shinko Shimomura, a father of 3 children and the Deputy Priest at Bodai-in Temple, says.

“There is no escape from the radiation contamination problem. If that is the case, I want to do the best I can for the future of our children.”

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), each person talks about one’s experience as if he/she were giving a self-introduction.

“At college, when I’m asked where I’m from and I tell them I’m from Fukushima, the most common response is “Are you OK?” It makes me feel a little uncomfortable.”

“The area I live in, the radiation level is low and so I don’t really consider myself a victim.” “I’d like to keep my mind neutral by listening to other people’s opinions, so that I won’t be biased.”

Together with her schoolmates, Aoi Seto, who goes to a high school in the city, is creating a CM to attract tourists to Iwaki. It is a project in collaboration with a travel agency.

“The realization that I am on the side that is telling people about the catastrophic earthquake led me to act.”

At one of the tables, the discussion is “How should we take in the current situation?”

“Perhaps we’ve come to a point where we should stop saying ‘Oh, no, no, no!’ and start voicing some positive attitudes.” “I believe that now is the turning point when the world is changing. The truth is that there are people smiling behind the people who are wailing that things are terrible.” “It just depends on how one can actually turn a bad situation into a good one.”

“I think we’ve all prepared ourselves for the worst and having done so, we are trying to think of ways to move on with our lives.” Yuichiro Kobayashi, the owner of a surf shop, has been clearing the Tsunami debris moments after the earthquake and has watched over the sea ever since. He conducts water quality inspections himself, but is concerned about the contaminated water draining into the sea from the nuclear power station.

“ Whether it’s local or out of the prefecture, people who have a passion for surfing will go out to surf if there’s a sea with waves.”

Seiji Nakamura, a fellow-surfer, is a photojournalist. At the beach, he showed us photos of scenes right after the earthquake hit.

“The town by the beach was burning as if it had been air-bombed. It was really terrifying.”

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), people change seats and continue their dialog. The participants say that by telling the people at another table about what they had talked about with the previous group, the dialog becomes deeper and is shared at the same time.

“Compared to before the earthquake, the big difference is that I am able to say what I really feel.” “Since the earthquake, the true nature of relationships with other people has been revealed.” “After the earthquake, we were blessed in many ways. Although I still have anxieties, I feel quite happy.”

“I’d like to find something that has come to being because of the earthquake.” Takeshi Matsumoto says. He is the one that started the Yoake-Ichiba, a restaurant district where shops full of energy and determination to boost and liven up Iwaki stand side by side.

“I’ve come to believe that if there is something I want to do, I should do it when I can. I intend to live my life to the fullest.”

At the stand-up bar Momo in the Yoake-Ichiba, Momoko Aikawa stands behind the counter, even though she is over 80 years old. She says that many of her regulars died in the earthquake.

“I am finally able to slowly talk about the earthquake. We’re all still trying so hard. It was only 2 years ago.”

The liveliness of the city of Iwaki in the past is a popular topic at the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting). The production of coal used to be the city’s key industry. “There used to be 3 department stores in the city. The coal mining and fishing industries were really big.”

“When I joined the company, it was right in the midst of changing its trade.” In 1966, when Kazuo Nogi joined Joban Coal Mine, a resort facility was opened. The company decided to shift its trade from coal mining to tourism.

“Since the olden days, the Joban region has been the supply depot for the Metropolitan area. Coal in the past, now nuclear energy.”

“There used to be huge crowds everyday.” Even to this day, the Hula Dance Show continues to be the star attraction. Remembered are the opening days, which became a movie featuring the first generation hula girls.

“It was the policy of the then president to hire the ladies of the miners. The closing of the coal mine was definite, and so the band musicians were also people from the mines. It was, in effect, an employment strategy as well.”

At “The Hula Girls Koshien Championship”, which started the year of the earthquake, high school hula girls across the country come to Iwaki to compete.

This is a signboard with a slogan saying to stand up against the nuclear power station accident. A rally to protest against the nuclear energy policy was being held in the station square.

At the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), there are many different attitudes toward the issues concerning the nuclear power station accident.

“I am so scared that there might be another accident at the nuclear power station.” “Why are they re-starting under these circumstances?” “The problem has not been solved yet.” “In my everyday life, I pretty much don’t look at the surveying instrument.” “As far as the radiation issue is concerned, there is no way to obtain a definite answer.” “I even have some regrets about the fact that I had not given it any thought until the accident happened.”

“If the radiation levels of the harvested agricultural products are below the accepted standard, some farmers ship the products to the market, but won’t eat them themselves.“ Says Yutaka Maruyama, who is a farmer that grows fruits in the city.

“When there is a shipment restriction, the one conveying the message speaks out loud and clear, while the receiver also listens intently. But the fact that a restriction has been lifted is made known to far fewer people than one might expect.”

“Whenever there was news of a shipment ban, however hard we tried to appeal that it wasn’t about us, many orders were cancelled.”

The nameko mushrooms that Naomasa Kamo grows are praised by dealers for its high quality, but he is still unable to break away from the effects of the accident. “The market price is still half or less than half of what it used to be before the earthquake.”

Fishery is also another one of Iwaki’s main industries. Ever since the nuclear power station accident, fishery remains shut down. At Kunohama port, fishermen work on the maintenance of their boats waiting for the trial fishing to begin. “In the bid for the Tokyo Olympics, they claimed that Tokyo is 200km away from Fukushima. That only means that they are going to abandon Fukushima.”

“I wonder if people would eat the fish we catch…” Then, he asked the students who were doing the interview, “How about it? Would you people eat them?”

There is not a soul at the fresh fishmonger. “I don’t sell fish from Fukushima at all and I carefully handpick my products. But still, no customers.”

“It’s not that I want somebody to do something about it. I just do what I do, one day at a time, thinking of how to go about this.”

In many parts of the city, election campaigns for the city mayor to be voted in a few days were going on.

Children can also be seen taking part in the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting).

“Which are you more afraid of, the earthquake or radiation?” “Well, the tsunami!” “I’m not that scared of radiation. There isn’t much of it now, right?”

Next to them, at the adults’ table, the topic is about the difficulties of raising children in Iwaki.

“My child said to me, ‘Why did you have a baby at a time like this?’” “Some parents want to let their kids play outside even if there are some risks, but some are absolutely against it.” “There are over 450 parks in the city, but only 11 have been decontaminated.”

“I came back from the place of refuge thinking that if we were careful, things should be alright.” Yoshida, who has a grade school daughter, tries to stay positive, but through the dialogs, she realized that she, too, is harboring anxieties.

“At home, she’s climbing trees that haven’t been decontaminated. But I think physical exercise and being stress-free are good things.”

“We don’t know if it’s from the radiation or not, but cysts have been detected in both my child’s and my thyroid glands.” Suganami is a lawyer and a mother of 5 children. She would like to avoid radiation as much as possible, but there is something on her mind that she keeps bothering her.

“Some people go about concerned about the radiation. But then, there are some that look away from the issue, or don’t even want to talk about radiation. They both have the right to freedom.”

Masako Ono, the director of a day-care center for children, says that she did everything she could, such as renewing the garden soil after the nuclear power station accident, to minimize the effects of radiation on the children.

“The reason why I decided to open the center 2 weeks after the accident was because there were people who could not move out of Iwaki. We have to accept that reality.”

The facilitator in charge of leading the meeting asks the participants.

“Many topics are being talked about. Having talked about them, what sort of a future do you have in mind?”

“It is definitely important to provide care for the children, but we must think of the grown-ups as well.” Kakuhisa Ono was working at a Junior High School near the shore when the earthquake struck. From a hilltop where he evacuated with the students, he witnessed the tsunami hit the villages.

“The children seem to be more emotionally hurt by the agonizing situation that their parents are in than about themselves.”

“In case of an earthquake, I had it ingrained in me that my job was to first and foremost convey the information to everyone.”

Michiko Sakamoto, who announced the occurrence of the earthquake on FM Iwaki, provided a lot of information through the radio right after the quake. “As time went by, there were unidentified dead bodies which had been severely disfigured, and I struggled to find appropriate words to convey these in the context of a regular program.”

“We are going to do something about what happened in our time. I’m glad it didn’t happen in our children’s era.” Hirokazu Ishii, who runs a fishing boat business, lost his father and beloved daughter in the tsunami.

“I was able to save my boat, but somewhere in me, I feel that because of that I lost my family. That’s why I am searching for the meaning of why I saved this boat.”

After the talking is over at the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), it is time for the results. Words by each participant are written on notepapers of different colors and posted on the wall.

“How to deal with and how to perceive the wall” was written by a college student who took part. Having said that there are many walls in Iwaki, he pointed out that the biggest one is the wall that stands between the people who have fled to Iwaki from other towns and the original citizens of Iwaki.

In the Izumi district of the city, there is an emergency temporary housing of 200 units in which evacuees from Tomioka-cho live.

“I love to cook”, says Shizue Sato, who lives alone in the temporary housing. She cannot help feeling homesick about the town where she used to live with her late husband.

“Of course I think about the house we worked so hard for. I want to go back and die in my own house. But I’m too old and I don’t know how much longer I can live.”

Mr. & Mrs. Nishihara play a leadership role among the resident volunteers. The husband, Kiyoshi, worked for a company affiliated with the nuclear power station. The wife, Chikako, thinks, though it was a dreadful accident, that they should not blame it all on Tokyo Electric, since they had, in some aspects, accepted its presence, too.

“I think it’s about time we stopped being sorry about what we’ve lost. If we count the things that we are left with and what we’ve gained since, they will lead us into the future.” After she said so, she sang us a Tomioka-cho folk song.

“It’d be nice if each person’s experience is passed on to future generations as individual stories.” Hikari Fujishiro, one of the promoters of the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting), continues to work on compiling the earthquake disaster experiences he has collected through interviews. About a month after the earthquake, he was inspired and has since been working on the project with his supporters.

“Being aware of the changing generations, I’d like to continue the Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) and the interviews for about 30 years.”

January, 2014. People clad in warm winter clothes are gathering at Bodai-in Temple. The Mirai Kaigi (Future Meeting) 2014 has started.

Among the familiar faces, there are some new faces, too. The next dialog for the future has begun in Iwaki.